Breaking the Cycle: Rethinking Artist EMPOWERMENT

September 1, 2025

6 MIN READ

“The saying goes...give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day; teach him to fish, and you feed him for life. For generations, institutions have handed artists the fish. Transformation takes root not only when artists learn to fish, but when building boats becomes a shared practice, and when artists co-steward the waters that nourish us all.”

Rika Iino, Founder & CEO, SOZO Impact Inc.

A System Tilted Toward the Few

The nonprofit industrial complex in the United States fuels the myth of the “struggling artist” while failing to provide dignified income, adequate resources, and long-term support. The pandemic laid these cracks bare. According to a 2020 Americans for the Arts report, artists’ average annual income plummeted from $33,000 to $13,500, a level well below the poverty line, with 55% depleting personal savings. A 2022 SMU DataArts study confirmed that artists consistently cite dignified wages as their most pressing concern.

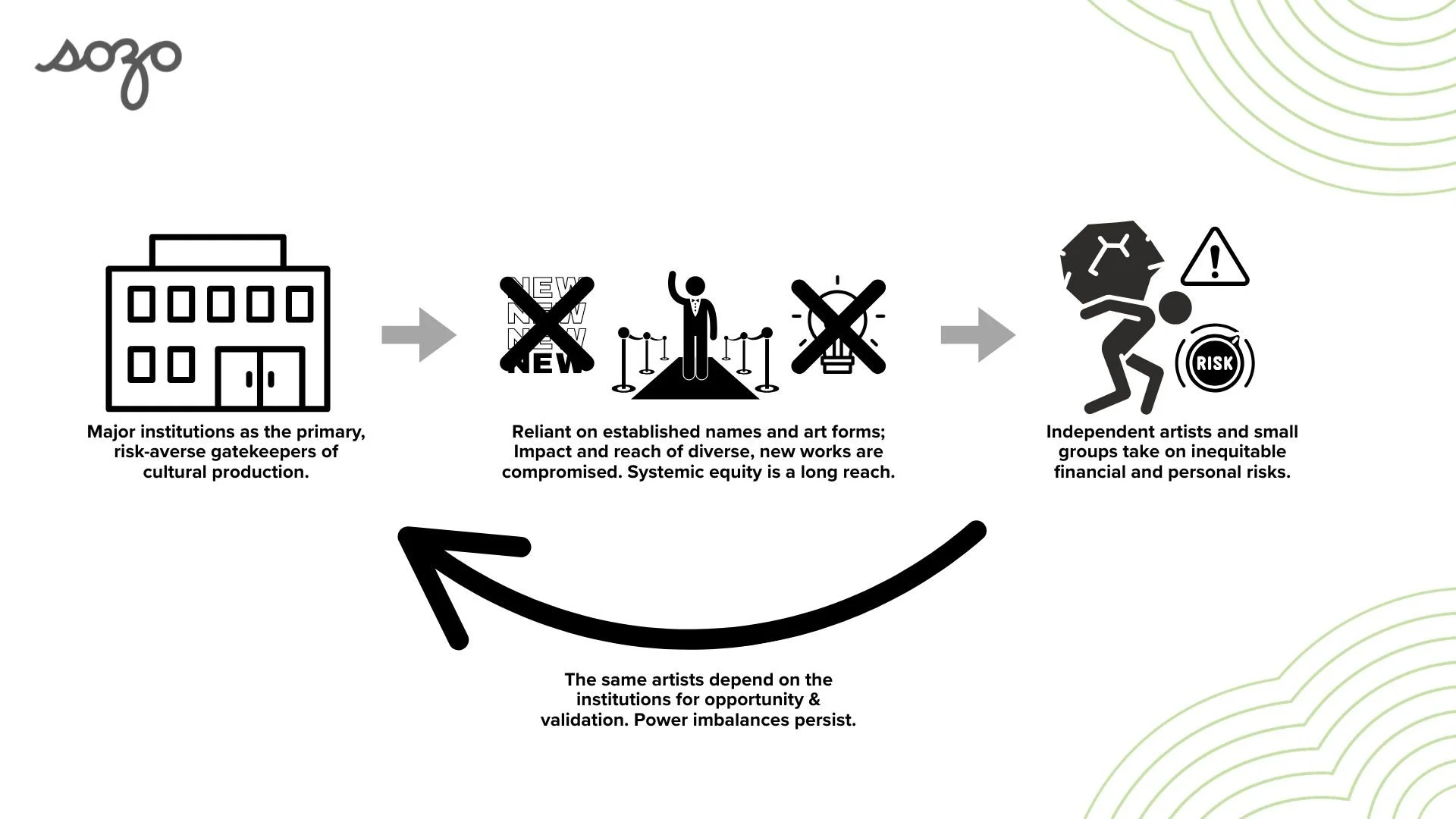

Institutions are essential cultural anchors, yet their role in artist support is often overstated—cast as arbiters of value and prestige. This aura can obscure the limitations of a system beholden to donor influence, box office pressures, and a reliance on celebrity to signal worth. With low risk tolerance, these structures face real challenges in investing more broadly in the creative ecosystem. The funds available to independent artists and small organizations cover only a fraction of what it truly takes to create, rehearse, perform, and lead in community, and artists often shoulder disproportionate financial and personal risk, with the burden falling heaviest on those from historically underserved communities.

The numbers speak loudly. A 2023 California Arts Council report shows that out of 13,774 nonprofit arts organizations in the state, less than 1%, or 108 of these organizations, with budgets over $10 million, absorb 70% of available resources. Half of all foundation arts grants and nearly three-quarters of individual donations go to these same large institutions. Just 4 of those organizations are BIPOC-centered organizations. And 5.9% of individual giving overall (including donations from trustees) goes to BIPOC-centered organizations.

This imbalance leaves artists—especially those practicing outside of established Eurocentric art forms—struggling for survival. Yet these same artists often must continue seeking recognition and opportunities from the very institutions whose systems for resources and visibility keep them in a cycle of inequity.

Persistent cycles of inequities and power imbalances normalize the “struggling artist” myth in the US.

The “Feast or Famine” Cycle

Independent contemporary artists in the non-profit sector depend on institutional grants, commissioning fees, and engagement opportunities, yet these rarely cover the full scope of production or operations. National programs such as New England Foundation for the Arts’ National Dance and Theater Projects, MAP Fund, and Creative Capital have provided vital support, but they are highly competitive, often underfunded, and tied to individual projects with time-limited horizons. Today, one of these programs has already ceased funding and another is set to sunset in the coming year.

The result is a relentless feast-or-famine cycle. Once a grant or engagement ends, so does the support. Between opportunities, artists shoulder an array of tasks without structural scaffolding: hiring collaborators, writing grants, negotiating contracts, managing insurance, and handling marketing—perennial work dictated largely by institutional terms and market-driven timelines rather than the rhythms of creativity or the needs of communities in co-creation. Even artists with managers or agents, whose models rely on transactional efficiency, lack sustainable working conditions and the holistic support needed to bring a work from concept to premiere to impact.

This cycle does not spare those artists who are in demand. Opportunities are often spread across seasons—sometimes years—in the name of rotating lineups. Similarly, grants are designed as one-off infusions rather than ongoing investment. The consequence is that both celebrated and lesser-known artists alike are locked in the same scarcity pattern: temporary bursts of support followed by long stretches of instability.

At the same time, the dominant norm within cultural institutions equates artist value with notoriety and box office performance. This “safe bet” mindset assumes artists must already arrive proven, ready-made, and marketable—an expectation that narrows the field of what is considered valuable, drawing on artists’ labor and creativity without investing in their sustainability. Those who push boundaries, experiment boldly, or co-create with communities outside of market-driven processes are even less likely to be acknowledged, and rarely resourced to their fuller potential.

Breaking this cycle calls for investing in the holistic arc of an artist’s journey—and with it comes a beckoning question: what becomes possible when artists are empowered beyond the institutional measures of value?

“Artists understand these systems were designed to neither empower nor sustain them. Yet voicing these truths is risky, as institutions enable access to stages, commissions, and validation. This pressure often leaves artists silent or resigned, normalizing power and resources flowing upward rather than circulating equitably.”

The Connective Infrastructure: An Opportunity

Since the 2020 cultural reckoning, institutions across the field have tested new approaches: expanding inclusive programming, loosening restrictions, and redirecting resources. The momentum of that period now faces headwinds, yet the lessons still point to what is possible. COVID-era Guaranteed Income programs, for instance, affirmed how meeting basic needs frees artists to invest more fully in their creativity. But the true return on these investments requires more than intermittent relief—it requires strengthening the connective infrastructure that sustains artists’ livelihoods as a whole.

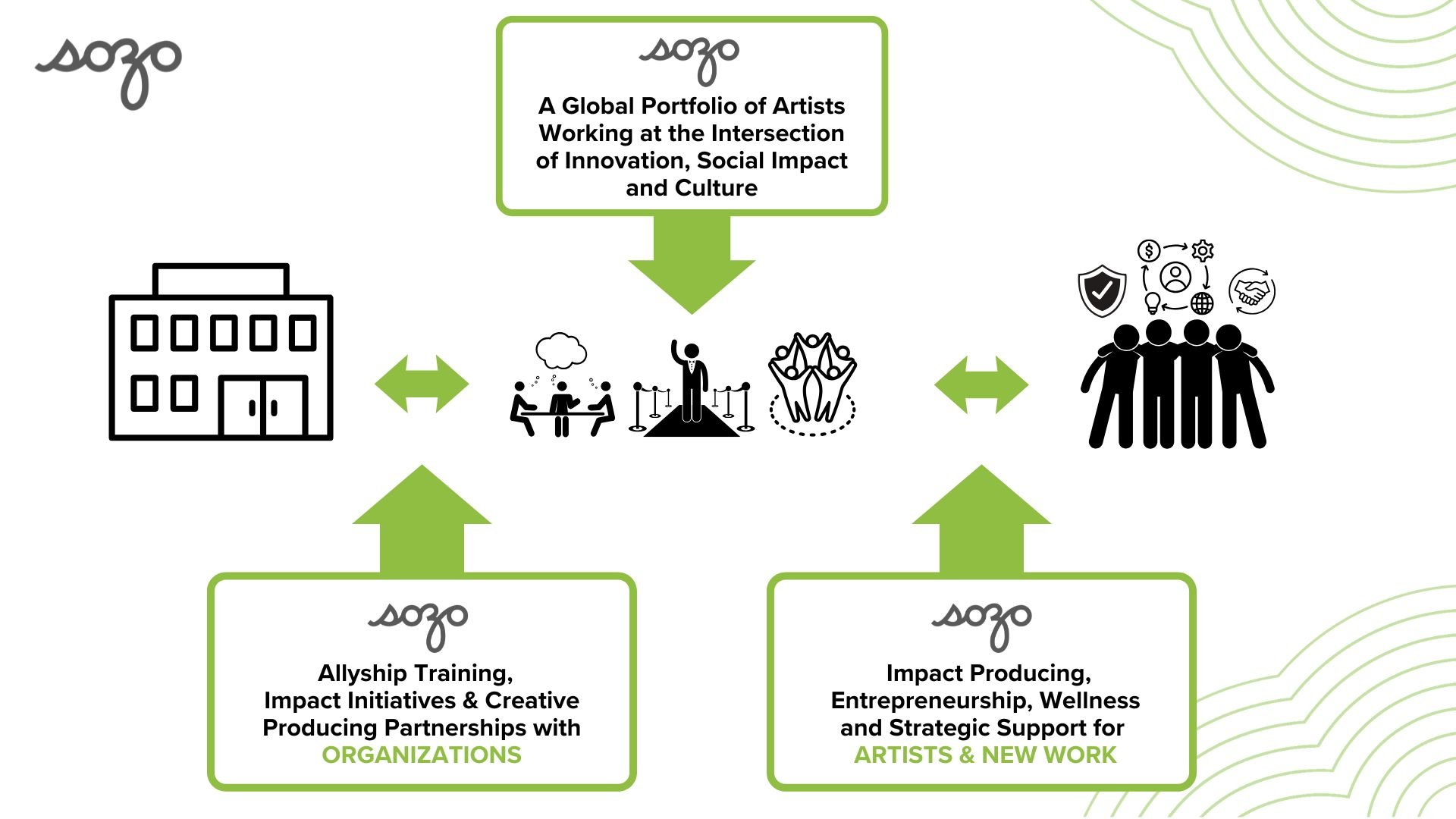

This is where SOZO locates its work. We approach our role as co-architects of a more equitable creative ecosystem, developing and distributing new works, designing programs that center and sustain diverse artists, and cultivating partnerships with institutions, corporations, and communities prepared to co-steward the future.

Across the US, emerging models like Artist Corporations, the Yale-born MOC Innovations, and artist-led hubs such as esperanza spalding’s artistic sanctuary are demonstrating how dignity, sustainability and care can shift from aspirational values to governing principles—and even, in some cases, be codified into law. SOZO situates itself within this long arc of change, committed to building the cultural landscapes where artists and creative sovereignty can thrive.

“Supporting both individual artists and institutions is essential. But the greatest opportunity lies in strengthening the connective infrastructure.”

SOZO’s 3-prong approach to strengthening the connective infrastructure for a more balanced and diverse creative ecosystem.

From Temporary Fixes to Rooted Longevity: SOZO’s Model

At a time when the field deeply investigates, and illuminates, the impact of the arts for public good—advancing health and social cohesion—the lived reality for the creative laborers who animate this value tells a more nuanced story. Too often, they shoulder the burden of transformation with only stopgap measures of survival. As government and corporations retreat from investing in inclusive culture, the weight of sustaining the arts, again, falls unevenly on those least resourced to bear it.

As the imbalance intensifies, so too does SOZO’s resolve to design another pathway forward. Since 2014 we have been laying the groundwork a systemic reorientation, designing structures that share risk fairly, resources that reflect the true cost of creation, and platforms that extend impact beyond institutional walls.

Our vision manifests as a next-generation 501(c)(3) agency shaped by a living tree model:

Roots (Incubator): supporting artists’ resilience and sustainability through entrepreneurial coaching and paid fellowships that rewire scarcity into sovereignty.

Trunk (Agency): advancing a robust portfolio of artists through new work development and touring, leveraging our global partner network to ensure resonance across geographies, sectors, and ideologies.

Branches & Canopy (Impact Accelerator): activating place-based impact producing where artists and communities cultivate co-belonging and wellbeing.

By blending philanthropic capital with a proven base of diversified earned revenue, this distributive model enables resources and impact to circulate like nutrients through a tree, each part interdependent, each reinvestment nourishing the whole.

This is SOZO’s connective infrastructure in action: a model where empowered artists flourish and culture becomes fertile ground for empathy, inspiration, and transformation, sustained not by rhetoric, but by deliberate, ongoing investment in the soil that nourishes artists’ lives and processes.

The time to anchor arts advocacy in artist empowerment is now.

A decade of persistence has brought us to this moment. With new initiatives underway—expanding our fellowship, diversifying our portfolio at the intersection of art and technology, and launching multi-year national impact programs—we invite you to join us in shaping what an artist-forward creative ecosystem can truly make possible.

—Rika Iino, SOZO Founder & CEO